The Foundation Doctor

Train the Trainer: The art of pedadogy

Among the many roles of being a clinician is the role of being a teacher. This is highlighted during your Foundation Training Years as you require evidence of your teaching role through the completion of a Developing the Clinical Teacher (DCT) form. This can be done through a formal presentation or teaching session and allows you to prove your teaching skills.

As you may already know it's not too hard to teach "badly" but it can be a challenge to teach "well". Try to think back to a lecture or teaching session that wasn’t “good” for whatever reason, be it the content, the presentation, or the setting.

On this page, we’re going to cover a few key points on how we can improve our teaching to try to prevent your audience from feeling the same way you did during that memorable session. This page is by no means exhaustive, but it will give you a flavour of how to improve your teaching styles.

What's covered on this page:

How can we teach more effectively?

- 1. Set Clear Learning Objectives

-

Learning Objectives explain what you want your audience to acomplish after engaging with your session. We can use Bloom's Taxonomy to help us with that.

-

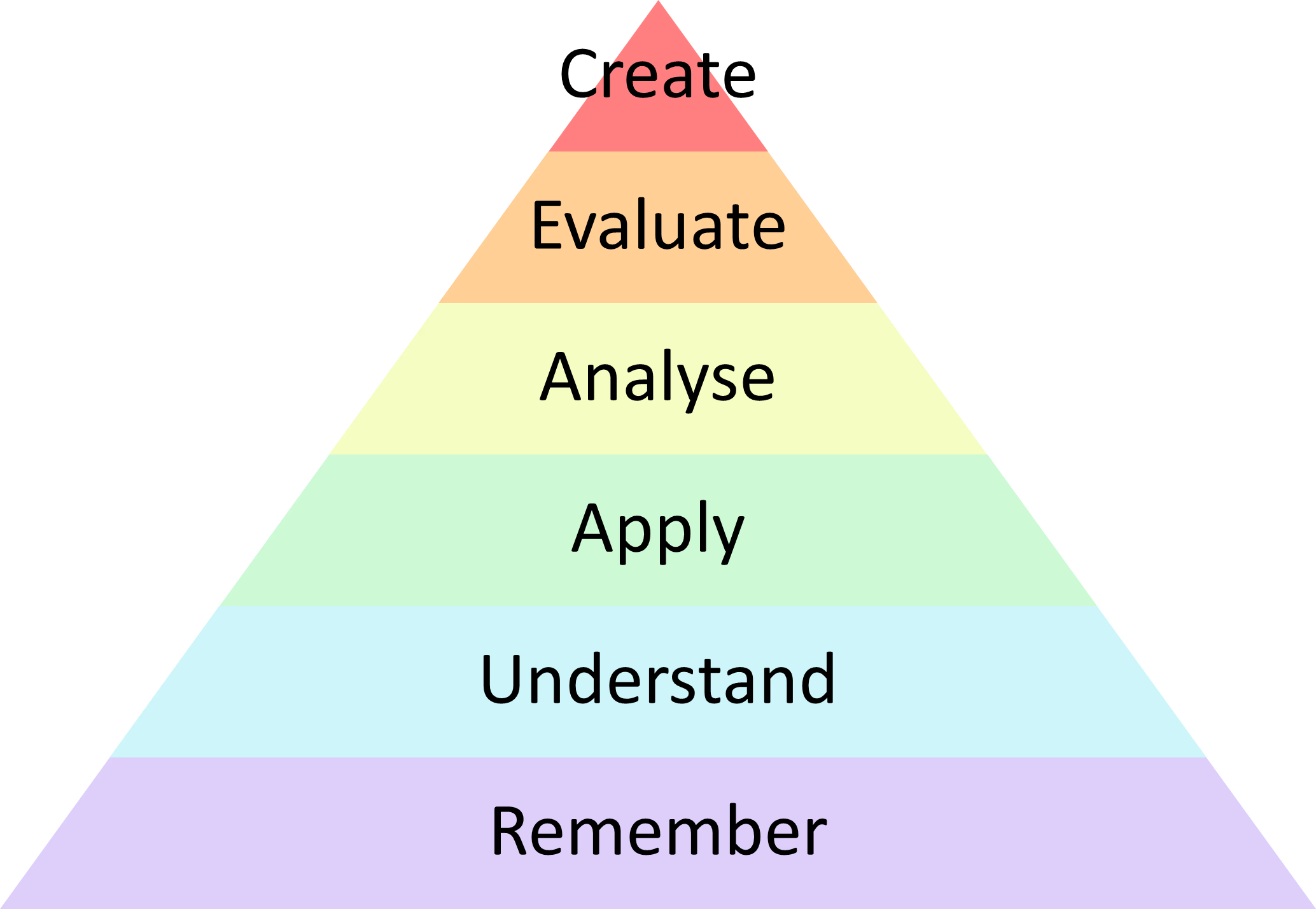

Figure 1.

-

Bloom's Taxonomy (as shown in Figure 1) can assist you in enhancing your teaching by guiding the creation of learning objectives that are specific and relevant to the cohort you are teaching.

For your beginner group, your objectives are likely to be situated lower down the pyramid. For instance, you might focus on having students summarise (remember and understand) a framework for classifying Neck of Femur fractures. However, for your expert cohort, you can aim to challenge them with objectives higher up the pyramid. For instance, you might task them with evaluating evidence between operative management strategies.

- 2. Consider Your Audience

-

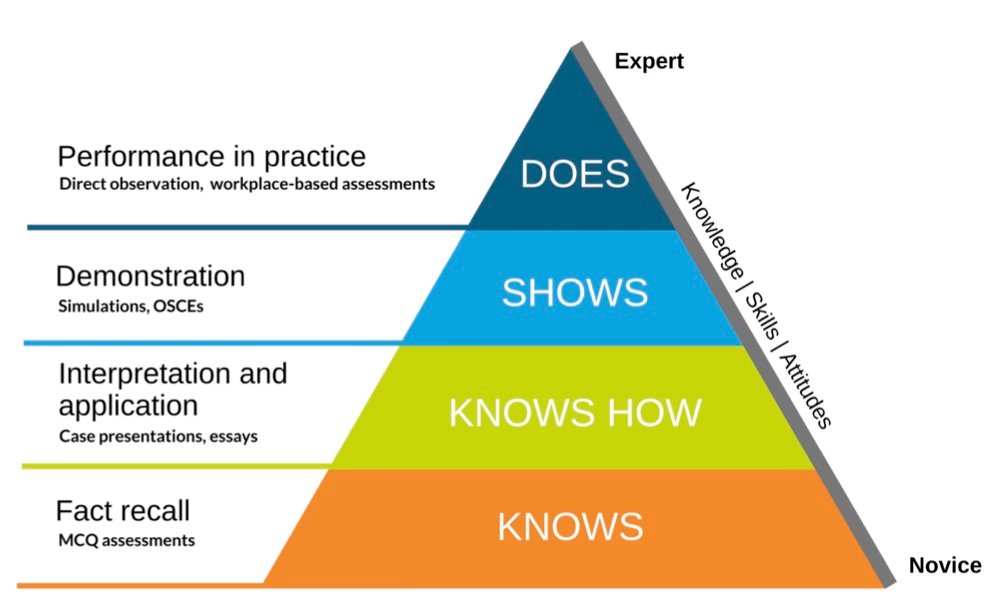

Figure 2.

-

Medical Education loves pyramids, so here's another. This is Miller's Pyramid of Clinical Competence. In summary, this pyramid helps us explain the difference between a Novice and an Expert. An expert will have the knowledge, skills and professional attitudes to naturally "do" something, for example, lead an arrest call. However, a novice student will be able to tell you how they would manage an arrest call. The difference is in the ability of the individual to apply this knowledge.

So, why is this important? When you consider what level of student you are teaching you can optimise your teaching style. So, if your students can already talk you through an arrest call it may be beneficial to prepare a simulated setting where they can show you. As a result, you can continue to target your learning objectives to the level of the learner. For example "To be able to apply knowledge of Avdanced Life support in leading an arrest call in a simulated environment."

- 3. Understanding Memory

-

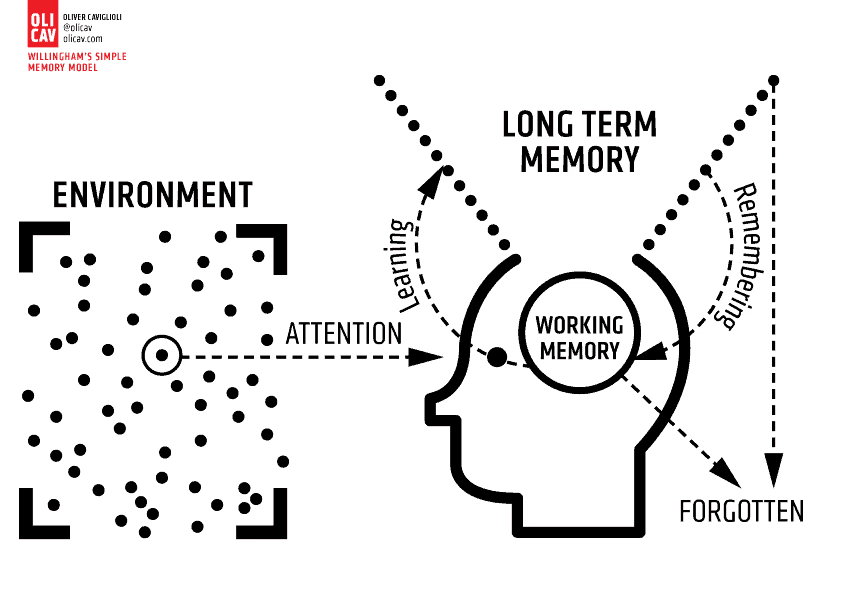

This theory underpins how the mind processes information. Understanding this will enable you to optimise how much your audience can learn.

When considering our memory, we have both long-term and short-term (or working) memory. Short-term memory is limited, typically to about 14 items, while long-term memory may be virtually limitless. This is relevant in our teaching setting because as we give information it's held in the short-term memory.

To understand this, take a look at Figure 3 below. Firstly, information is taken in from the environment. It is then held in short-term memory where it is either stored in long-term memory or lost.

Figure 3.

With this understanding of how our memory works we need to think about how we can utilise this for teaching and learning.

- 4. Strategies To Improve Learning

- Reduce distractions in the room.

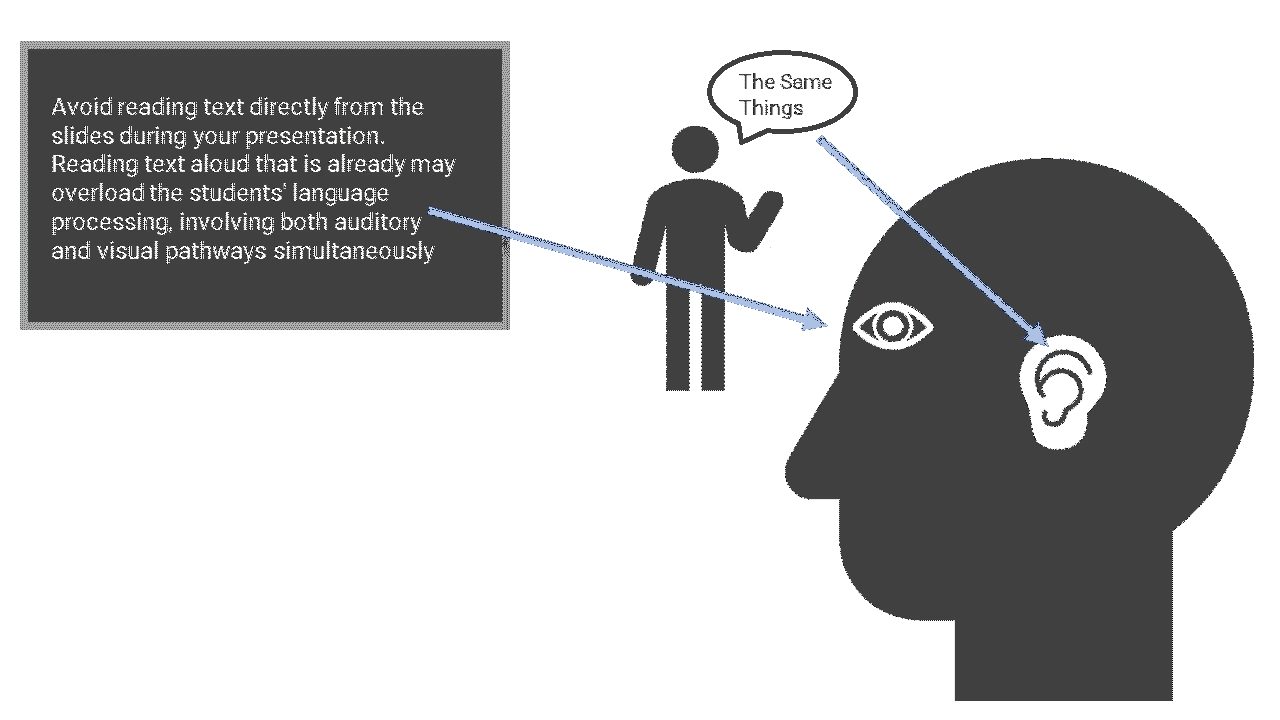

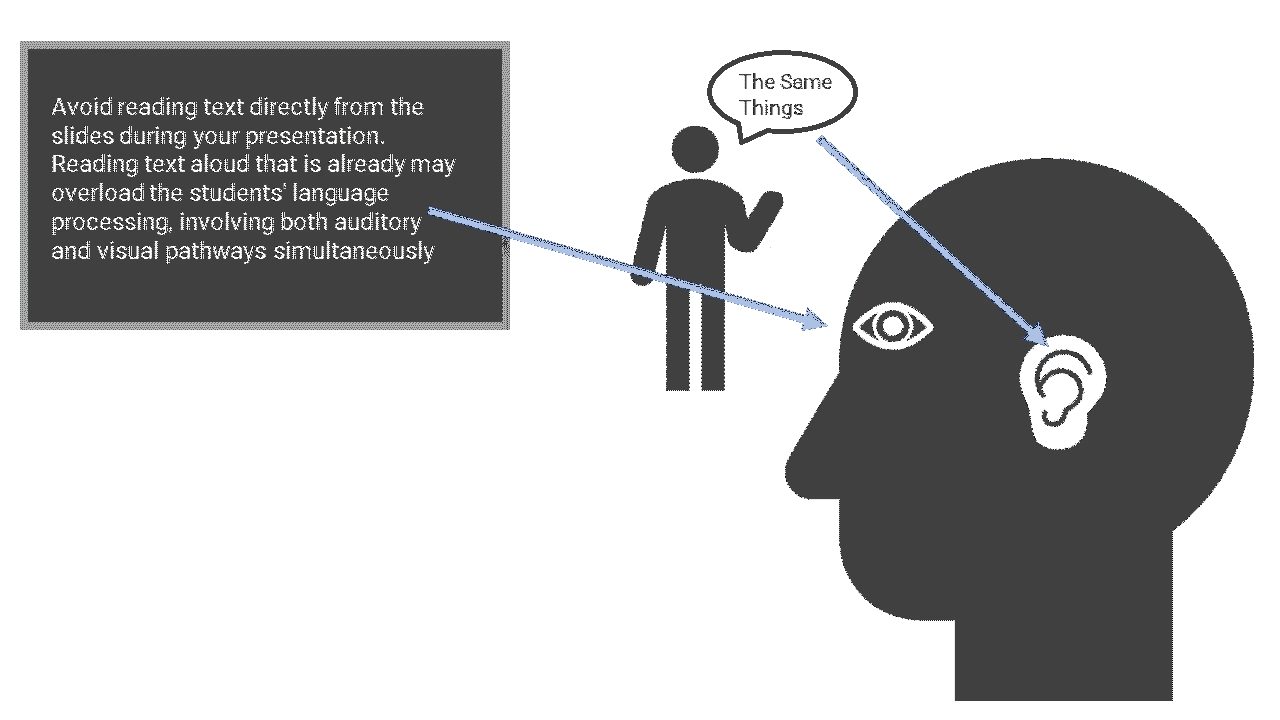

- Avoid reading text directly from the slides during your presentation.

- Avoid Transient information

- Utilise the Coherence Principle

- Utilise the Signalling Principle

- Incorporate examples into your teaching strategy. For novice learners, provide worked examples, while for more advanced students, encourage problem-solving. To delve deeper into this concept, you can explore 'The expertise reversal effect'.

Check Understanding

Ensure a baseline understanding for all students at the start of a teaching session to optimise learning. For example, when teaching a medical student about venous cannulation, gauge their current knowledge before beginning the lesson. Asking a baseline question, like recalling the veins of the forearm, can help capture the audience's attention. Some students will be familiar, others not, allowing for a brief recap to ensure everyone is on a similar level. Repetition aids knowledge retention for those familiar, clarifying points for those with some understanding while introducing new concepts to others.

Key Tip: Handouts can be very useful to ensure a baseline of knowledge before your session, this allows you to focus on more detailed topics.

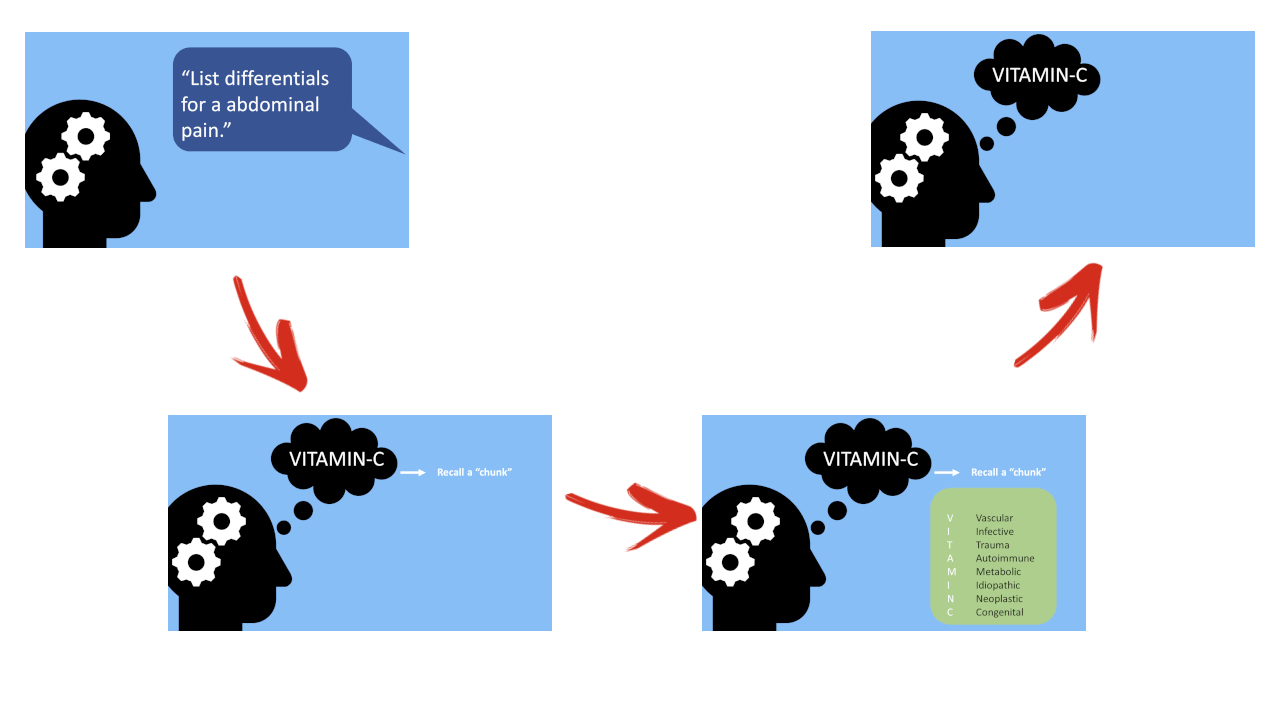

Chunk Information

To overcome limitations in working memory, we should chunk information into sections of memory (called schemas) for longer-term storage. For instance, instead of presenting a list of differentials for students to remember for abdominal pain, you could teach them the surgical sieve, such as VITAMIN-C. Next time the student is asked about differential diagnoses they will recall the schema (VITAMIN-C) linked to this.

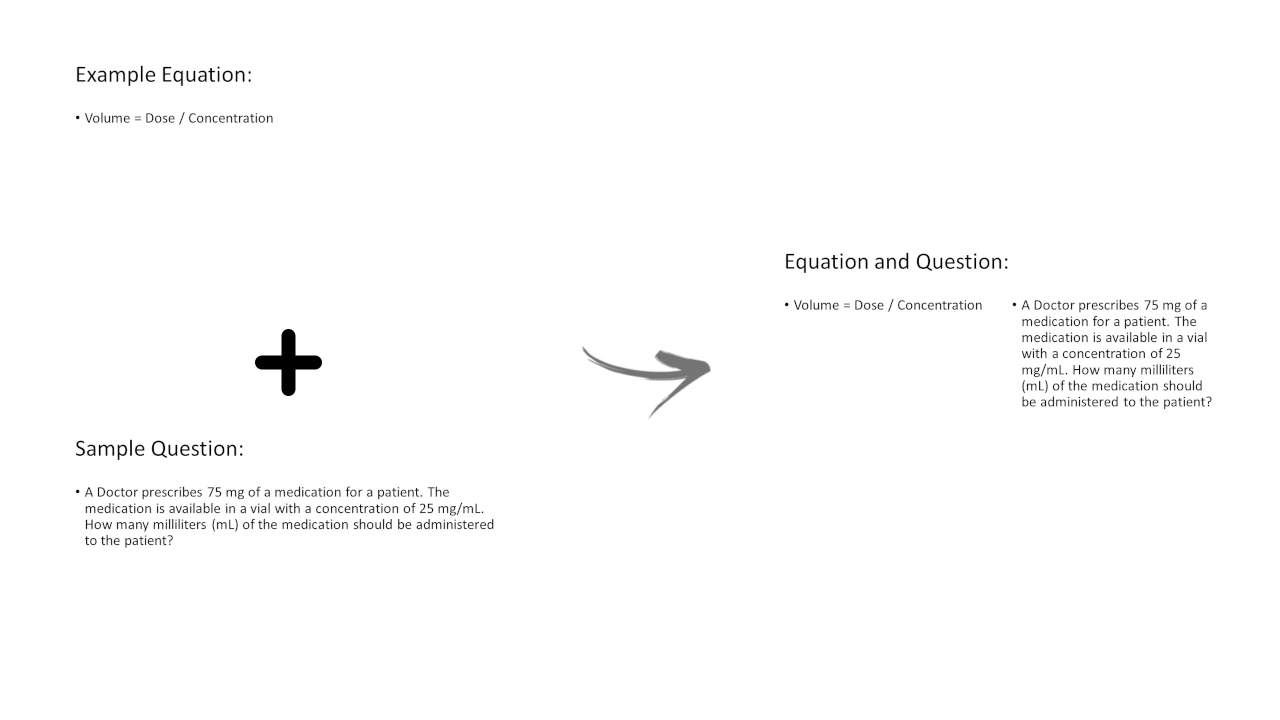

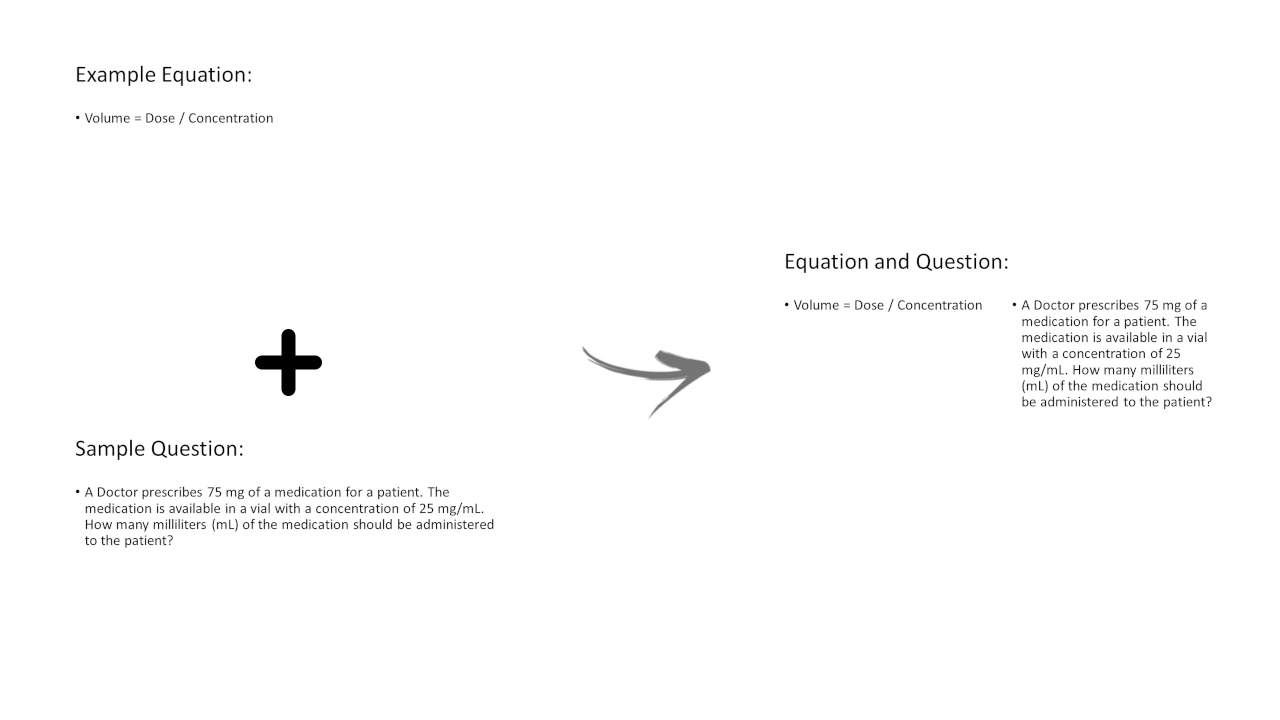

Figure 4.

Use Examples

To overcome limitations in working memory, we should chunk information into sections for longer-term storage. For instance, instead of presenting a list of differentials for students to remember for abdominal pain, you could teach them the surgical sieve, such as VITAMIN-C.

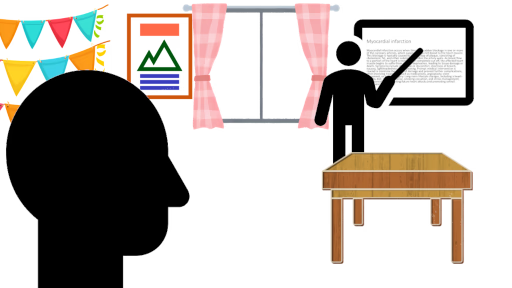

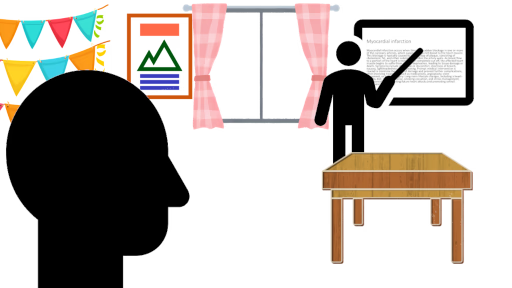

Think about distractions to learning

Okay, you've captured their attention and brought the students up to speed. Now, let's consider the 'extraneous load' in cognitive load theory, which refers to unnecessary information that detracts from core learning taking place. To optimise learning, we must reduce extraneous load while enhancing intrinsic load (simplifying the complexity of new content) to allow for the processing and integration of new knowledge with previous learning for storage in long-term memory.

There are many ways you can reduce unnecessary distractions from learning:

This includes that model skeleton in the corner, flip charts, posters, signs, and anything that is not directly related to your teaching. While it may not always be feasible to remove all posters or signs from the wall, you can minimize distractions. For instance, altering the environment, such as relocating students to an empty side room, may prove more effective than teaching in a ward bay.

Reading text aloud that is already displayed may overload the students' language processing, involving both auditory and visual pathways simultaneously. This can result in presented information being redundant. Instead, consider utilising both visual and auditory pathways at the same time. Returning to the cannulation example, you can articulate the steps while demonstrating the procedure. This approach engages students more effectively than simply listing the steps on slides.

Ensure that the content you discuss appears on slides simultaneously as you present it. For instance, in a pharmacology teaching session covering drug dosing calculations, display the equation concurrently with the practice question. If information is presented sequentially, it becomes challenging for students to recall details from the initial slides, leading to increased mental effort, higher extraneous load, and a reduction in learning.

Want More Strategies?

In Summary, to improve your teaching you should:

- Target learning outcomes to your learner

- Chunk information

- Reduce extraneous load

- Check understanding regularly

- Engage with pre-teaching

- Create handouts

- Present relevant information when necessary

What to do if you want to learn more?

Take a look at this article summarising the ABCDE of Cognitive Load Theory

If you've found the contents of this page useful then you may be interested in looking for local courses, for example, the Post-graduate Certificate in Medical Education.

References:

-

Sweller, J., van Merrienboer, J. J. G., & Paas, F. G. W. C. (1998). Cognitive Architecture and Instructional Design. Educational Psychology Review, 10(3), 251–296. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022193728205

-

Lovell, O., & Sherrington, T. (2020). Sweller’s Cognitive Load Theory in Action. John Catt Educational, Limited. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/nottingham/detail.action?docID=6461837